Introduction

Texas Tech Softball Head Coach Craig Snider and his coaching staff are making waves in their second year with the Red Raiders, smashing records along the way. With a wealth of experience primarily in offensive strategies, Snider brings with him 21 seasons of coaching from renowned programs such as Oklahoma, Florida State, and Texas A&M. His tenure includes mentoring an impressive 20 All-Americans and orchestrating three Women’s College World Series appearances, culminating in a championship win while at Florida State in 2018.

In his first year at Tech, Snider and his newly formed team shattered multiple program records, including the single-season home run record, the most doubles in a season, and the single-season slugging percentage.

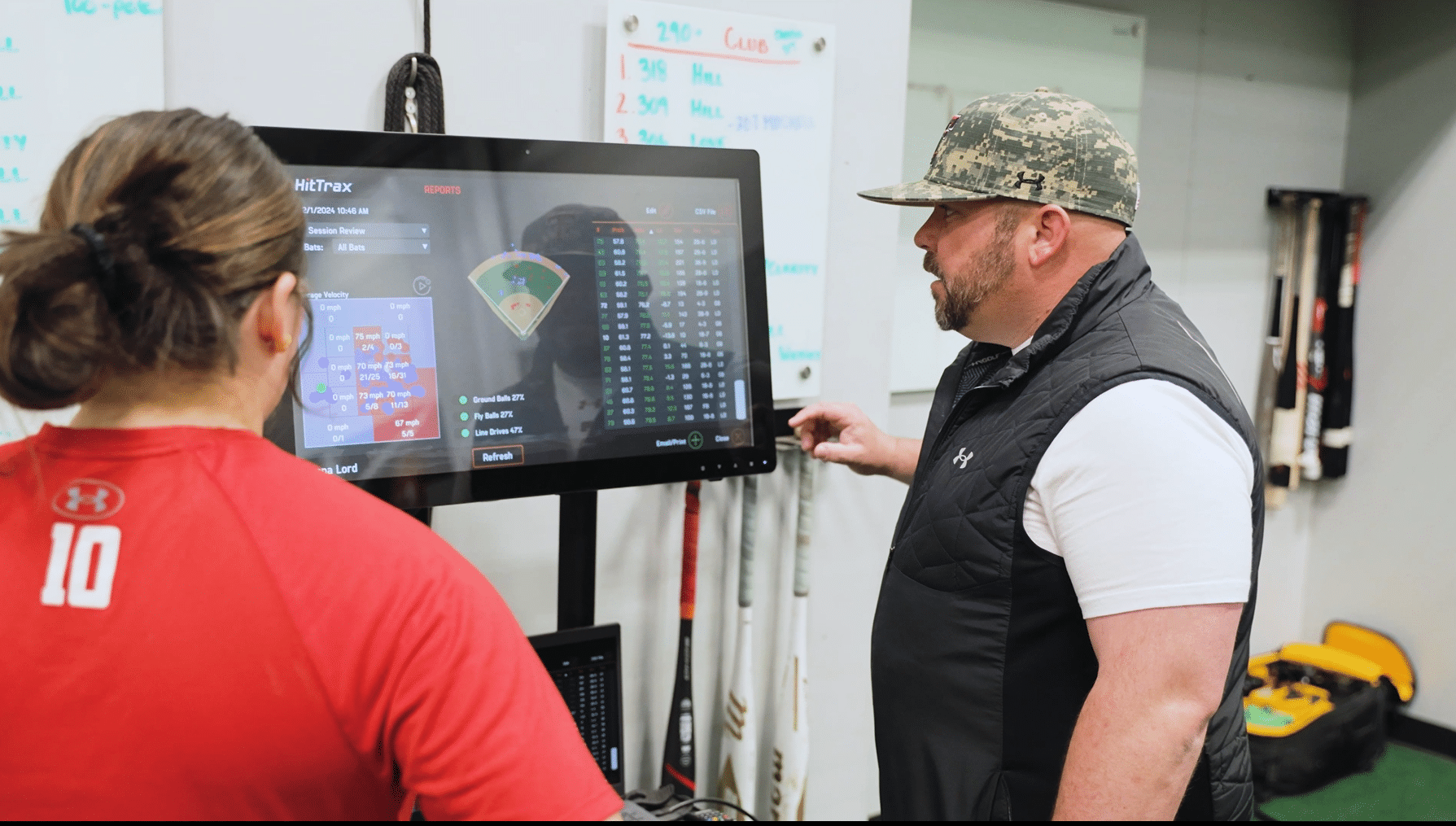

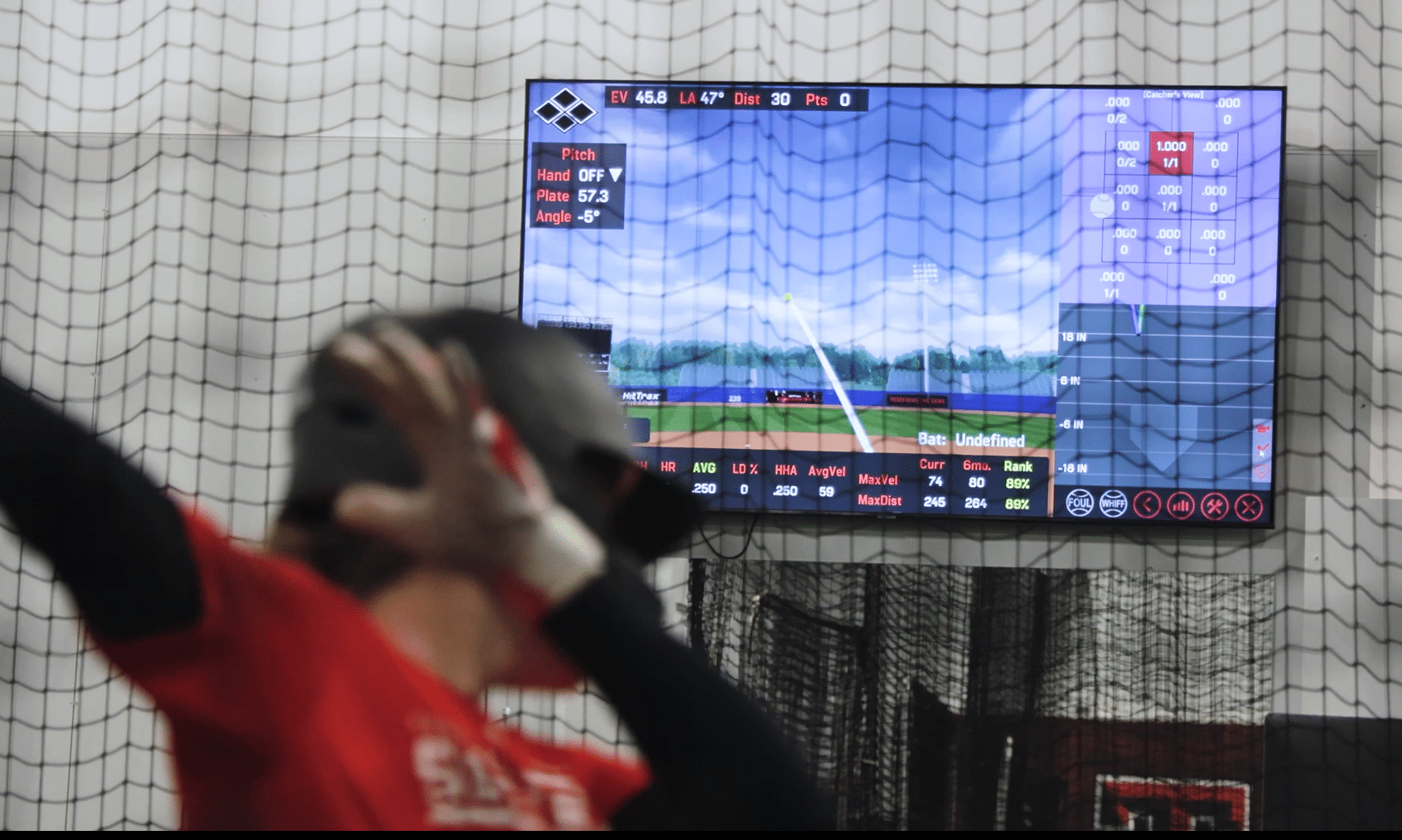

Snider has been immersed in HitTrax technology for the past four years, reveling in the instant feedback it provides on batted ball data. The ultimate focal point of their training target as a program is to increase exit velocity. He often emphasizes, “As long as we hit the ball hard, we are going to be okay.” In Texas Tech’s hitting facility, Craig and his staff maintain an exit velocity leaderboard, driving players to continually strive for personal records. Alanna Barraza, a graduate student, shares her experience: “Last fall, I was determined to make it onto the leaderboard. As someone of my stature, it’s not always easy, but when my numbers hit 80mph and 260ft, I was finally up there! However, the bar keeps rising, making it increasingly challenging.”

During Snider’s inaugural offseason, he introduced HitTrax Biomechanics to his players, embodying a philosophy of curiosity towards new technology, experimenting with offensive strategies, and identifying correlations and trends. He posed the question, “Can we extract data that may benefit us?”

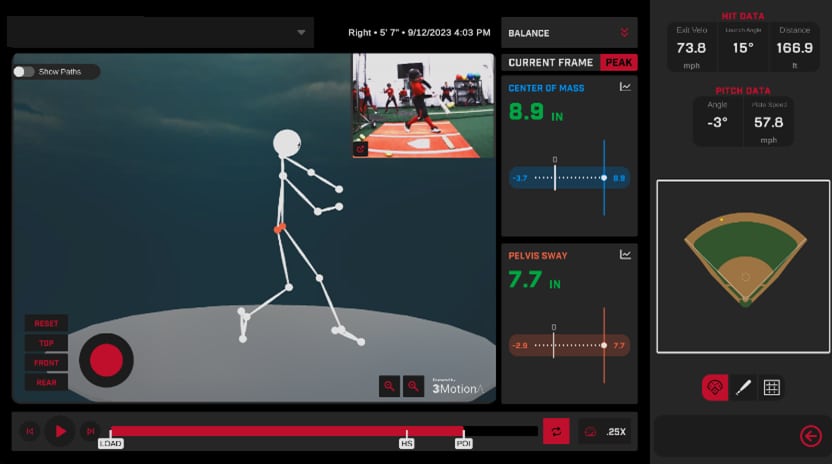

Players underwent their initial biomechanical assessments at the onset of the offseason, repeating them just before the season commenced. Snider and his team meticulously analyzed the data, pinpointing areas for improvement. If a particular issue surfaced, they tailored specific drills to enhance players’ mechanics.

Keep reading to learn more about touch points that Coach Snider focuses on when utilizing the biomechanics module.

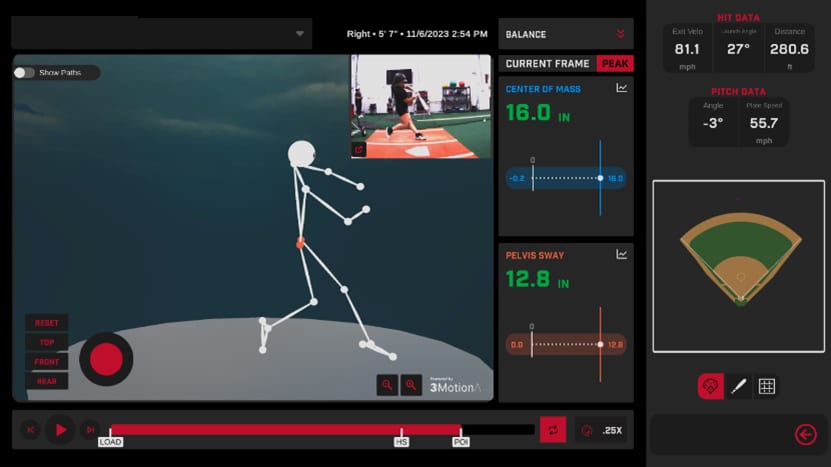

1. Center of mass

When working through order of operations, Coach Snider first looks to a player’s ability to move mass. To define, the Center of Mass (COM) is the total forward movement through the swing from load to point of impact. COM will typically indicate a player’s ability to control their weight shift through their load phase to ensure their upper body is in a good position to hit at heel strike. From heel strike to the point if impact, COM will then indicate if that player can translate their linear movement to rotational movement.

Coach Snider focuses first if a player has too much or too little weight shift for their swing or power potential. Too much, and you’ll see a lunging effect in the swing. Too little, and you’ll typically see a player leaning back with their upper body at heel strike. Either way, it leads to inefficiencies.

The example of the player above introduces a first-year athlete at the beginning of the fall season on the left and at the end of the fall season on the right. Knowing there was a significant amount of power not being tapped into, Coach Snider focused on getting more weight transfer through the swing. This athlete went from 8.9” of COM movement to 16” of COM movement. The result is a 6 MPH jump in exit velocity in this swing (and overall, a 13 MPH increase to Max EV by the end of the fall). With this increase in COM, Coach Snider next looks to stride length to ensure load stays synced up.

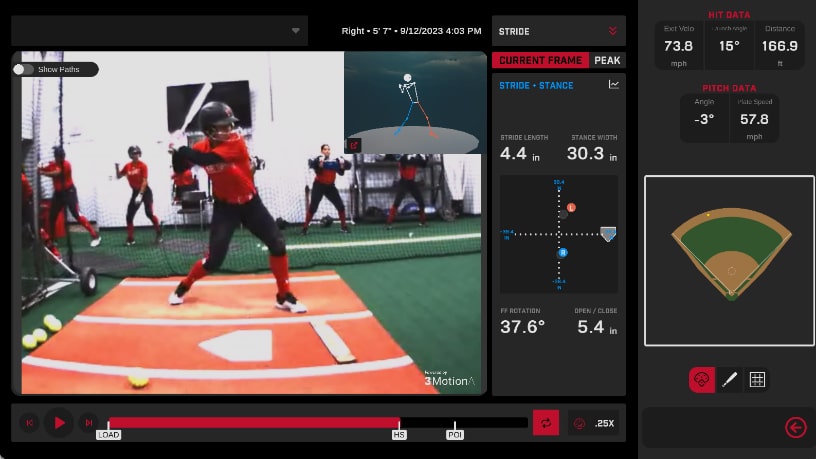

2. stride

Stride length varies dramatically from hitter to hitter. While some hitters opt for large pre-pitch movement and stride, others opt for no-stride. What we know is that all hitters move some amount of mass in their load phase, and that all hitters goal is to be in the best possible position to hit at heel strike. What Coach Snider has correlated, is that when a player’s peak COM matches (or is close to) their stride length, they are putting themselves in the best and most balanced position to hit at heel strike.

To continue our example from above, in cases where Coach Snider adjusts a player’s COM, he also pays attention to the impact on stride length trying new positions and loads until the players is comfortable and moving well. You’ll note in this example, this athlete had a significant increase in COM and therefore needed to add a significant amount of space to their stride (4.4” to 18.7”).

Once his athletes are moving mass and landing well, he next looks to head movement to ensure they’re seeing the ball effectively.

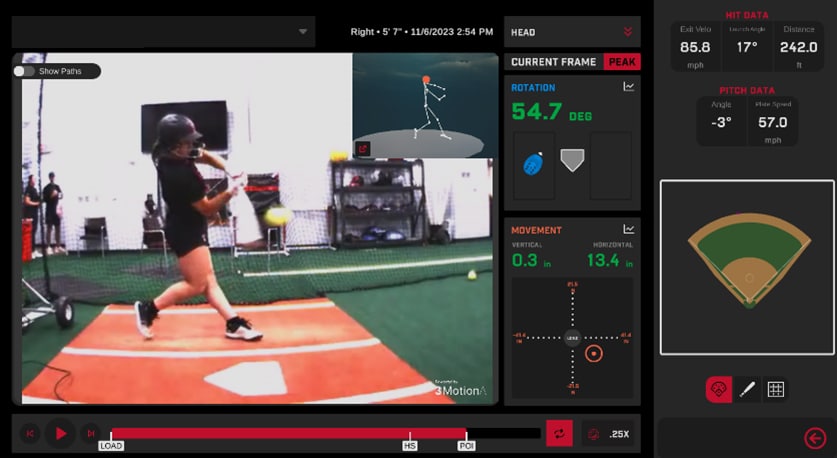

3. head movement

Coach Snider says the name of the game when it comes to head movement, is to keep the players eyes on plane. From his perspective, when the head drops, the eyes drop. When the eyes drop, the ball moves significantly more than it is. When working with his hitters in the HitTrax biomechanics module, Coach uses the terminology ‘keep the circles touching’. This refers to the diagram indicating head movement throughout the entire swing. His goal for his players is that through their load phase their head stays level in terms of vertical movement. From heel strike to point of impact, he’s looking for minimal (if any) head movement (vertical or horizontal). As you’ll note, by the end of the fall this athlete has only .3” of total vertical head movement throughout her swing which indicates that her eyes are staying totally level through her swing.

If all things so far carry, his players now have moved mass, are balanced at heel strike, and on plane with their eyes. The next checkpoint is posture to the pitch.

4. torso

Coach Snider’s final checkpoint from load to heel strike relates to a player’s posture. Posture is expressed through measurements of forward bend and side bend. Forward bend will vary depending on level of the pitch. Higher pitches in the strike zone will see slightly less forward bend, lower pitches may see slightly more forward bend. ‘Maintaining posture’, relates to a player’s ability to translate peak forward bend into side bend throughout the swing. Variance between the two will indicate a player is ‘dipping’ with their upper body or standing up through their swing.

As you can see in the example above – at heel strike, you see this athlete set their swing at a 33.3-degree forward bend. On the image to the right, you see that forward bend translate into 30.7 degrees of side bend. This is an excellent example of a player holding posture through their swing (resulting in a 241 ft. ball – a homerun in any park).

Coach Snider feels if he can get his players here – from load to heel strike with efficient COM movement and stride length, eyes on plane, and swing posture set, then they’ll be in the absolute best possible position to sequence their swing through contact generating the maximum amount of exit velocity upon contact.

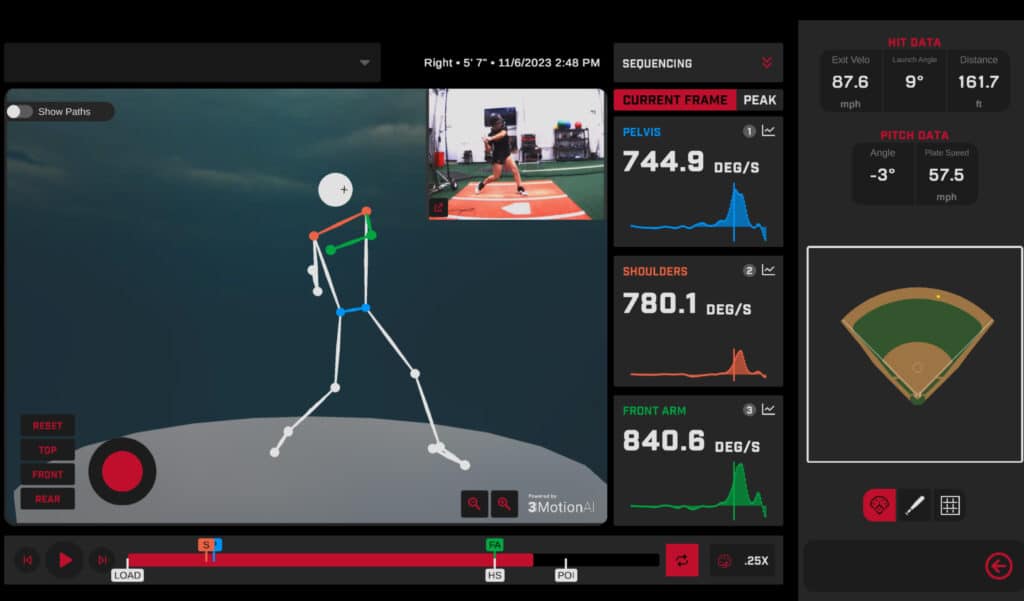

5. sequencing

Sequencing is how a batter generates and transfers speed throughout the body from heel plant through point of impact. In most effective swings, each segment (rotational acceleration of pelvis, toros, and arms) builds off the previous segment to produce/increase rotational acceleration as it travels up the kinetic chain through barrel release. This is reflected through peaks of acceleration and deceleration as each part speeds up, then slams on the brakes to transfer the acceleration up through the body. The further apart the peaks, the more energy the player will see through their barrel release. This transfer of energy maximizes rotational acceleration, bat speed, and ultimately exit velocity.

To note, proper sequencing can also produce repeatability and consistency in a hitter’s swing. It can improve swing decisions, giving the player’s body more time to either commit or hold off before contact. Simply put, great hitters’ sequence well.

Coach Snider’s perspective is this though – efficient sequencing cannot happen without the proper setup to the swing. If a player can get to heel strike in a good position to hit, that’s when you’ll see optimal effects of great sequencing.

From there, there are many common reasons why a player’s sequencing can be off. Some are mechanical issues and others are problems with mobility. Once you start asking these questions, you can begin to put the puzzle pieces together to get a more accurate assessment of each athlete on your roster and deliver a personalized plan for improvement.

conclusion

In summary – Coach Snider uses HitTrax ball flight data as his barometer for offensive improvement, and biomechanics as his roadmap to get there. After looking at these five metrics of his hitters’ swings, he and his staff formulate individual training plans. It’s less about knowing the answers and more about exploring new ways to unlock potential.

The Texas Tech softball team is bought into the test and retest approach constantly looking to raise the bar year to year. As an example of this, look no further than their team exit velocity leaderboard. Last year the entrance point to top 10 was 80 mph. This year, players need to be at 85 mph to get their names up. Ultimately this reflects Coach Snider and his staff’s relentless pursuit of growth while utilizing all the tools at their disposal to do so. When speaking about the team’s success last year, Snider said this: “It can be highly contributed to what we’ve done with HitTrax and them understanding how to move, what to swing at, how to swing, and chasing that exit velocity.”

With the 2024 season underway, the team looks to break more records and to keep improving every day.